Still producing those hateful anti-Muslim stereotypes after 1,400 years

“Will the Islamophobia never end?”

asks Robert Spencer at

Jihad Watch. The reference is to the assassination of the mayor of Kandahar, Afghanistan by a suicide bomber with explosives hidden in his turban.

Just, like, you know …

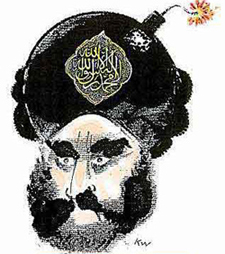

Reinforcing Islamophobic stereotypes

This is, of course, the famous, harmless cartoon for which Muslims have declared a death sentence against Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard and have made repeated attempts against his life. In 2010,

an axe-wielding Somali broke into Westergaard’s house where his five year old granddaughter was staying with him. Fortunately Westergaard’s bathroom had been outfitted as a safe room with a steel door, which the Somali kept trying to break through with his axe until the police arrived.

All Westergaard did was draw a cartoon. As for the real bomb-in-turban wearing Mohammaden, The Guardian reports:

Afghan insurgents appeared to continue their assassination campaign against key public figures on Wednesday with the killing of the mayor of Kandahar.

Ghulam Haider Hamidi was targeted by a suicide bomber who got into the municipality compound in Kandahar City with explosives concealed under his turban. The technique was first used earlier this month in a mosque in the city during a memorial service for Ahmed Wali Karzai, a regional strongman and half-brother of the president.

Abdul Manan, a municipality employee, said the mayor had emerged from his office into the garden, where he made a call on his mobile phone.

The assassin grabbed him and detonated the bomb. [cont.] (That is, the story continues, but not the mayor of Kandahar, nor, obviously, his assassin.)

And speaking of the murder of Muslim leaders with whom “we” (meaning the anti-Western leaders of the West) have allied ourselves, this was

reported in yesterday’s

New York Times:

BENGHAZI, Libya—The top rebel military commander was killed Thursday, and members of his tribe greeted the announcement with gunfire and angry threats. The violent outburst stirred fears that a tribal feud could divide the forces struggling to topple the Libyan dictator, Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi.

The leader of the rebels’ provisional government, Mustapha Abdul Jalil, announced Thursday evening without providing details that unnamed assassins had killed the commander, Gen. Abdul Fattah Younes, and two other officers.

General Younes, a former officer and interior minister in the Qaddafi government, had long been a contentious figure among the rebels, some of whom doubted his loyalty. He had been summoned to Benghazi for questioning by a panel of judges, and members of his tribe—the Obeidi, one of the largest in the east—evidently blamed the rebel leadership for having some role in the general’s death.

The specter of a violent tribal conflict within the rebel ranks touches on a central fear of the Western nations backing the Libyan insurrection: that the rebels’ democratic goals could give way to a tribal civil war over Libya’s oil resources. Colonel Qaddafi has often warned of such a possibility as he has fought to keep power, while the rebel leaders have argued that their cause transcends Libya’s age-old tribal divisions.

Before General Younes defected to the rebel side soon after the uprising began in February, he had been a longtime friend of Colonel Qaddafi. Libyan state television sometimes tried to exploit speculation about his divided loyalties by reporting that he had returned to his old job.

During an interview in April, Colonel Qaddafi’s daughter, Aisha, suggested that General Younes was still loyal to her father. She said that at least one former member of the Qaddafi government on the rebels’ ruling council was still talking with the Qaddafis, and she pointedly declined to rule out General Younes.

For months, a public rivalry between General Younes and another rebel military leader, Khalifa Hifter, contributed to the pervasive sense of chaos in the ranks, as both men claimed to command the fighters in the field.

Rumors about General Younes and intertribal tensions started picking up here in the rebels’ de facto capital early Thursday evening with reports that a group of four judges working for the rebel council had summoned General Younes for questioning. The war effort he led has stalled out for months along immobile battle lines on the eastern front.

When the rebel leadership announced a news conference later at a Benghazi hotel, a few dozen members of his tribe gathered outside and began chanting. Some inside warned of possible violence if General Younes were removed from his position.

Instead, two hours after the press conference had been scheduled to begin, Mr. Abdul Jalil announced the death in a carefully worded speech that left many scratching their heads.

Mr. Abdul Jalil confirmed that General Younes had been summoned for questioning by the judges, though he declined to say why. He said only that General Younes had been “released on his own recognizance,” rather than either accused or exonerated of anything.

Mr. Abdul Jalil said that an armed gang had killed General Younes and the other two officers, and that at least one of the gang members had been captured. He declined to name the killer, or to say whether the gang had been working for Colonel Qaddafi, rebels who did not trust General Younes or some other tribal group or faction.

Mr. Abdul Jalil then added that the rebel security forces were still searching for the bodies of the three dead officers, raising questions about how he had confirmed their deaths.

But the rebel leader also conveyed an unmistakable anxiety about the feelings of the Obeidi, General Younes’s tribe. Instead of appearing with other members of the rebel council, as expected, he sat at a table with men he said were elders of the Obeidi. He repeatedly said he wanted to “pay respects” to the tribe for its sacrifice and understanding, calling it “strong and deep.” He left the news conference without taking questions. [cont]

Posted by Lawrence Auster at July 30, 2011 08:11 AM | Send