The body of Richard III found

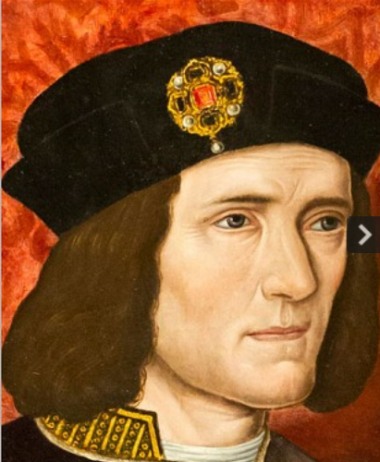

Richard III.

Not the monster of the Tudors’ and Shakespeare’s invention.

It is reported that the skeleton of King Richard III (1452-1485) has been discovered buried underneath a town council car park in Leicester. But the article in the

Telegraph does not adequately explain how the team of scientists have identified the remains as Richard. It refers to DNA testing, but does not say what the DNA testing shows. Indeed, the author of the piece is so stupid that he says that the Wars of the Roses—which Richard’s death at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 brought to a conclusion—lasted two years, when in fact they went on for a generation. British journalists must be the worst in the world.

Wikipedia to the rescue:

Archaeological investigation

On 24 August 2012, the University of Leicester and Leicester City Council, in association with the Richard III Society, announced that they had joined forces to begin a search for the remains of King Richard. Led by University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS), experts set out to locate the Greyfriars site and discover whether his remains were still interred. The search appeared to locate the Church of the Grey Friars, where Richard’s body had been buried, beneath a modern-day city centre council car park.

Site of the Greyfriars Church, Leicester. The skeleton of Richard III was recovered in September 2012 from the centre of the choir, shown by a small black dot.

In parallel, the British historian John Ashdown-Hill used genealogical research to track down matrilineal descendants of Anne St. Leger, Richard’s only sororal niece whose line of descent is still extant. A British-born woman who migrated to Canada after the Second World War, Joy Ibsen, was found to be a 16th-generation great-niece of the king. Although Ibsen died in 2008, her son Michael gave a mouth-swab sample to the research team on 24 August 2012. His mtDNA, passed down on the maternal side, can be used to compare samples from any human remains from the excavation site, and potentially to identify King Richard.

On 5 September the excavators announced that they had identified the Greyfriars church and two days later that they had identified the location of Robert Herrick’s garden, where the memorial to Richard III stood in the early 17th century. Human bones were found beneath the church’s choir. On 12 September it was announced that a skeleton discovered during the search might have belonged to Richard III. Five reasons were given: the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; there was severe scoliosis of the spine, possibly making one shoulder higher than the other (to what extent would depend on the severity of the condition). Additionally, there was an object that appeared to be an arrowhead embedded in the spine; and there were perimortem injuries to the skull. Dr. Jo Appleby, the archaeologist who discovered the skeleton, described the latter as “a mortal battlefield wound in the back of the skull”

On 4 February 2013, the University of Leicester confirmed that the skeleton was beyond reasonable doubt that of King Richard III. This conclusion was based on DNA evidence (including comparison with DNA from a 20th-century relative), as well as physical characteristics of the skeleton that were highly consistent with contemporary accounts of Richard’s appearance. The team announced that the “arrowhead” apparently discovered with the body was a Roman-era nail, probably disturbed when it was first interred. However, there were numerous peri-mortem wounds on the body. Part of the skull had been sliced off with a bladed weapon. This would have caused rapid death. The team concluded that it is unlikely that the king was wearing a helmet in his last moments. The Mayor of Leicester announced the king’s skeleton would be re-interred at Leicester Cathedral in early 2014.

Here, from the same article, is an account of Richard’s desperate, courageous death at the Battle of Bosworth Field, where the 331-year dynasty of the Plantagenets (and Medieval England itself) was brought to an end and Henry Tudor, crowned Henry VII, became master of England and the initiator of the Tudor despotism:

The switching of sides by the Stanleys severely depleted the strength of Richard’s army and had a material effect on the outcome of the battle. Also the death of John Howard, Duke of Norfolk, his close companion, appears to have had a demoralising effect on Richard and his men. Perhaps in realisation of the implications of this, Richard then appears to have led an impromptu cavalry charge deep into the enemy ranks in an attempt to end the battle quickly by striking at Henry Tudor himself. Accounts note that Richard fought bravely and ably during this manoeuvre, unhorsing Sir John Cheney, a well-known jousting champion, killing Henry’s standard bearer Sir William Brandon and coming within a sword’s length of Henry himself before being finally surrounded by Sir William Stanley’s men and killed. The Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, says that a Welshman struck the death-blow with a halberd while Richard’s horse was stuck in the marshy ground. The blows were so violent that the king’s helmet was driven into his skull…. Richard III was the last English king to be killed in battle.

Polydore Vergil, Henry Tudor’s official historian, would later record that “King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies”.

I’ve often seen Richard described as the last English king to be killed in battle. However, I’m not off-hand aware of any other English king—that is, any other king after the Norman Conquest—who died in battle.

If you are interested in learning about Richard III and the Wars of the Roses, I highly recommend Richard the Third by Paul Murray Kendall (1956), one of the most fascinating books I have ever read.

- end of initial entry -

Derek C. writes:

Richard I (Lionheart) was killed by an arrow during a siege in France. It’s not quite like the Battle of Bosworth Field, but it was combat.

A reader writes:

I was disgusted, but not surprised, to see this in an accompanying Telegraph article:

“David Monteith, Leicester Cathedral Canon Chancellor, said the remains would be re-interred early next year in a Christian-led but ecumenical service.”

I had to read this twice, as when I saw the word ecumenical, I thought, “Of course, this will be a joint Anglican-Roman Catholic ceremony, given that Richard was a Catholic but he is being buried in an Anglican Cathedral.” But of course, it says “Christian-led but ecumenical,” implying a multi-faith arrangement. Will Muslim and Hindu rites be performed at the reburial of Richard III? Hopefully, this is merely an another example of British journalistic inexactitude, and they simply mean an ecumenical Christian service, as I first assumed. But given that Leicester is the first English town to become majority-minority, and that we are dealing with the contemptibly craven Church of England here, there is a fair chance we will see the first (but not almost certainly not last) burial of an English head of state in which in Imam takes part.

February 7

Mark L. writes:

Yesterday I picked up a used copy of Paul Murray Kendall’s Richard III, as per your strong recommendation. I can’t put it down—I’m already about a quarter of the way through (the Earl of Warwick has just been killed in battle). Thanks so much for this recommendation.

It never occurred to me that Shakespeare’s monster is almost completely fictional. I figured of course that he was a caricature, but if any of my professors or colleagues ever suggested that Richard was a victim of character assassination by the Tudors — “the politics of personal destruction” — I don’t remember it.

Since graduating with my M.A. in English in the mid-’90s, most of my reading has been along more spiritual lines. It’s a welcome diversion to look into the history of this fascinating period, on which my knowledge is pitiful. Kendall was a magnificent scholarly writer.

As you once told me in a previous correspondence, there is no substitute for reading, no short cuts to gaining useful knowledge. Obviously you’re right. Between the demands of work and a young family, I can scarcely find the time to sneak off and devour a book. But you’ve whet my appetite … maybe this will get me going again.

Jason R. writes:

If you’re interested, Channel 4 broadcast quite a compelling documentary on the story of the discovery of Richard III’s body.

Posted by Lawrence Auster at February 04, 2013 08:37 AM | Send